By Eric Gaus of Dodge Construction Network

As Halloween approaches an economist can think of no scarier thing than the likelihood of a stagflation event. Stagflation is a combination of a stagnant economy coupled with high levels of inflation. Unfortunately, should the US economy succumb to recession it is very likely to be stagflationary. This presents a problem for the surety and re-insurance business because in such an environment contractors are likely to go out of business and the cost of the construction will increase. Therefore, it’s likely we will see more defaults on surety contracts while the costs of execution are rising.

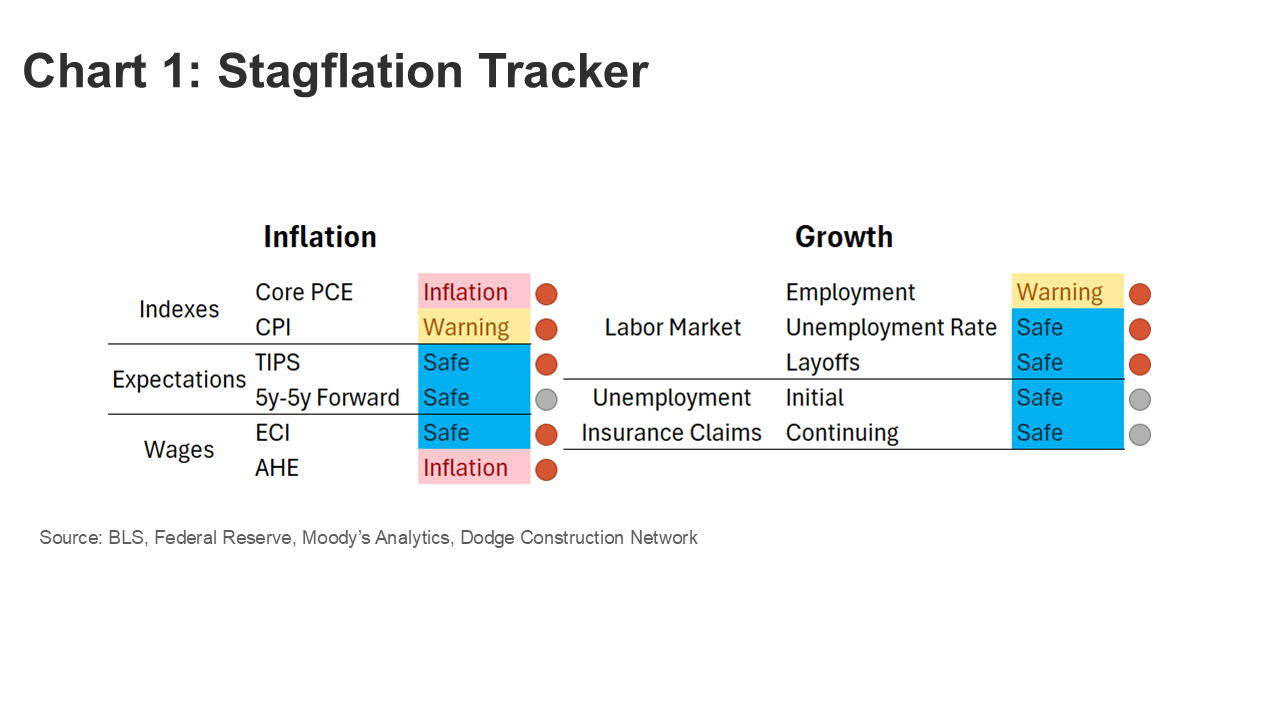

We are not yet in a stagflation environment, but we are eerily close. Inflation, as measured by core personal consumption expenditures, is over a percentage point above the Federal Reserve’s target of 2% and almost all underlying measures of inflation are heading in the wrong direction. The labor market is in an uncomfortable place too. While there is a less clear signal given the shrinking labor supply, most other labor-related measures are also deteriorating.

Dodge’s baseline forecast (most likely outcome) does not assume recession, just anemic growth and slightly higher inflation. However, given the relatively high probability of stagflation we conducted a “what if” scenario exercise on our national forecast model to see how the various construction sectors would be impacted. The results we present below will be relative to our baseline to help illustrate the marginal impact of a stagflationary environment.

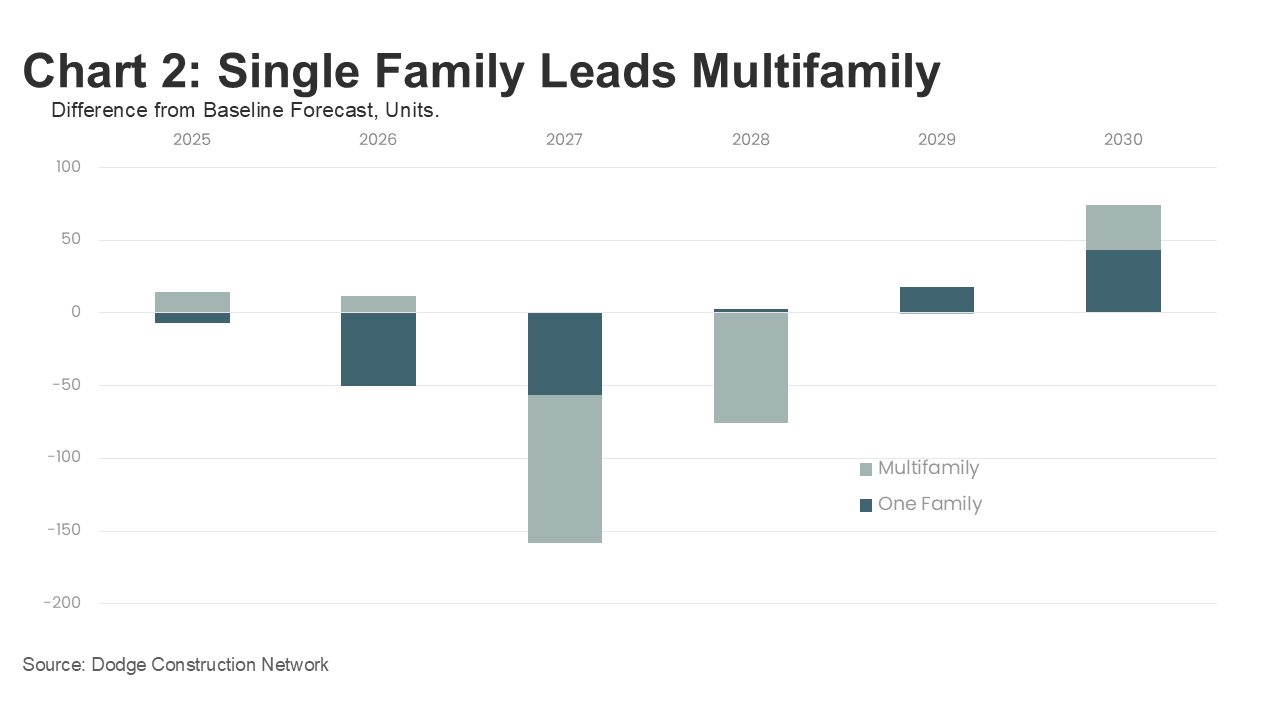

Not too surprisingly, the residential sector gets hit first and harder than the non-residential sectors, but it also recovers sooner and faster. A similar story holds true across each residential sector, where single family units fall first, but recover faster. Homebuyers would react quickly to higher inflation and a weakening job market, remaining on the sidelines during a stagflationary recession, while builders would also face constraints from higher costs and less labor. Additionally, the larger multifamily projects would not stop on a dime, in part due to sustained demand for more affordable rental units and multi-year construction timelines, but these projects also are harder to restart. The net loss over the 5-year horizon of our exercise comes to about 120 thousand housing units.

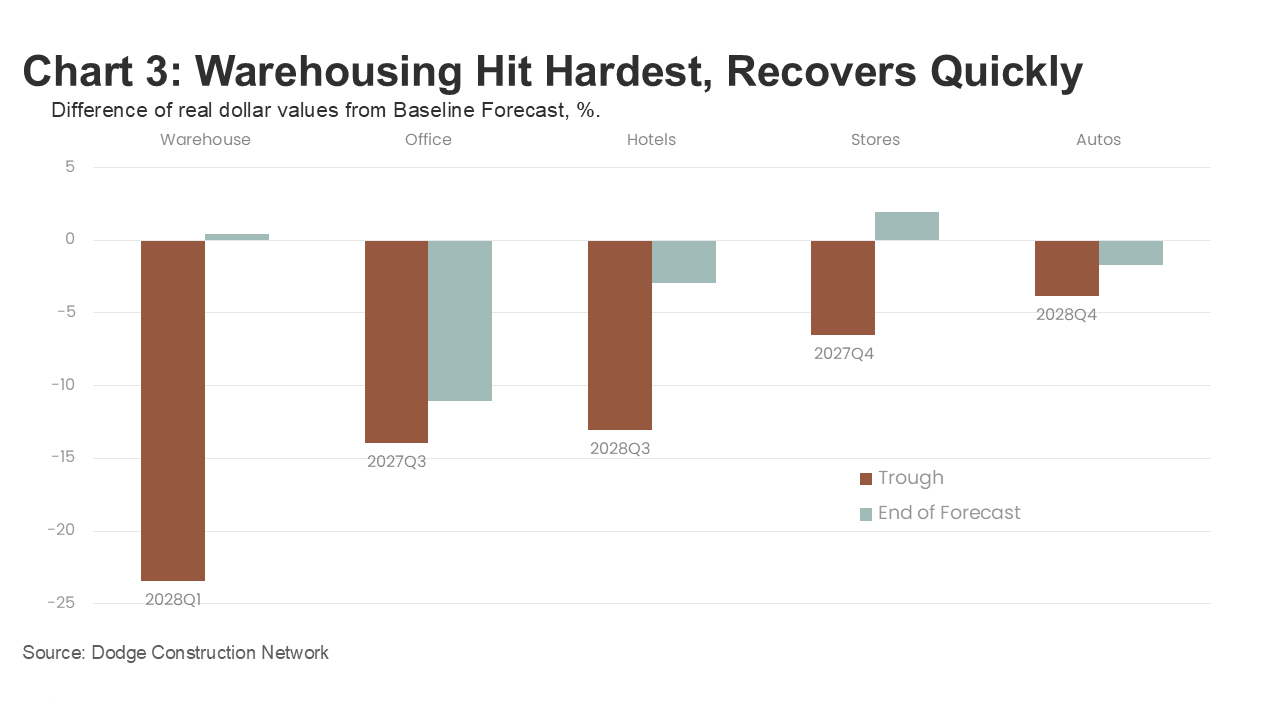

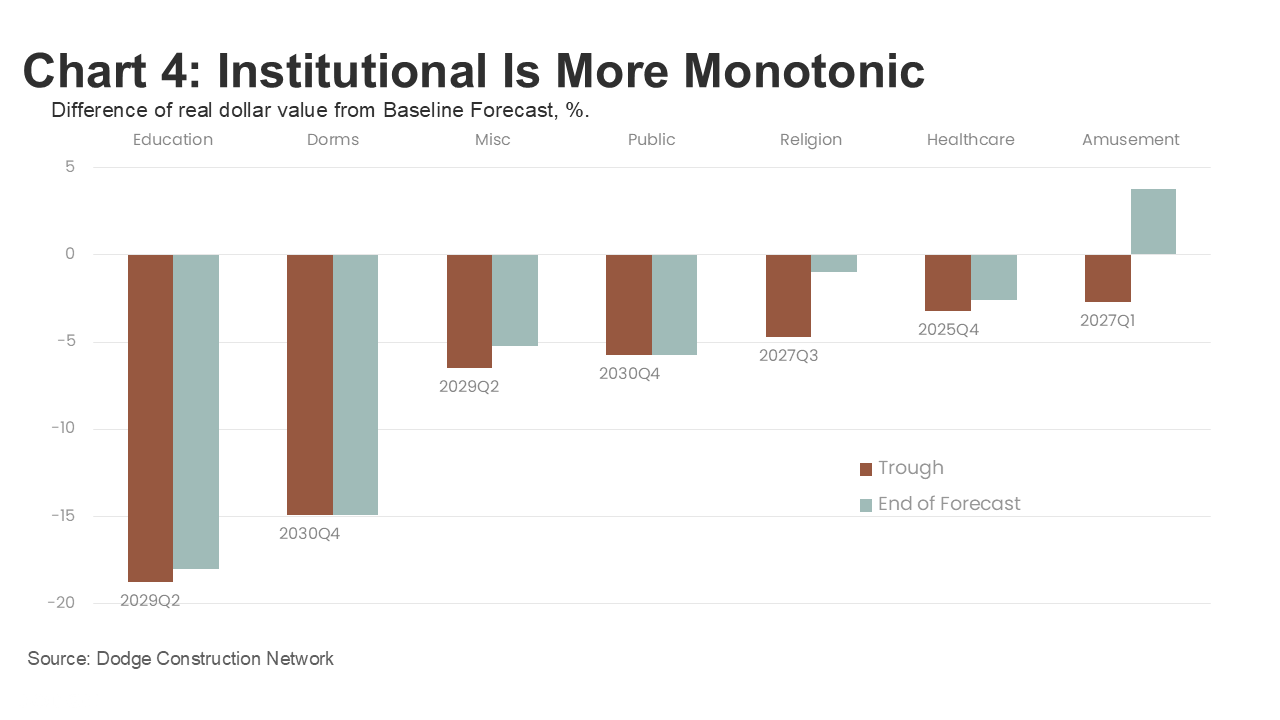

In non-residential construction there is a difference between how the commercial and institutional respond. Institutional buildings, which includes education, dorms, health care, public, religious, amusement, tend to have longer investment horizons and more public funding and therefore it takes longer for the full impact to come to bear and consequently suffer the most long-term losses. In contrast, commercial construction, which includes office, retail, warehouse, hotels and parking/auto service stations, is more dynamic leading to larger short-term losses, but faster recoveries.

On the commercial side, warehousing gets hit very hard, but recovers fully by the end of the forecast, whereas office buildings, with the second deepest trough, barely recover. Commercial sectors would collectively face rising cost pressures amid slower consumer spending and business investment. The warehouse sector, in particular, is likely to have the toughest time overcoming labor shortages and supply chain disruptions. The graph below shows the peak decline along with the quarter of that trough, as well as the relative standing at the end of the forecast. Note that these numbers are in real dollar terms so we are taking into account inflation.

Four of the seven categories for institutional buildings find their trough in the last 6 quarters of the forecast window. This is indicative of a slow-moving group that benefits directly or indirectly from government funding and therefore tends not to react as quickly to economic weakness as housing or commercial segments. The downside is that by the end of the forecast period only one category has recovered. These long downturns mean that institutional building would be the most underbuilt of all the categories, with education being the most disrupted.

Despite the rather scary story line, the upside is that as of now the specter of stagflation remains a risk as opposed to the baseline. And as long as we account for the potential fallout we can, to some extent, mitigate that risk. One way to mitigate risk is appropriate sizing of new opportunities by adjusting, based on the relative risk, the mix of contracts underwritten. For example, if the current portfolio skews towards single family, one might favor multi-family contracts in the near term. Alternatively, one might consider balancing re-insurance contracts based on the risks for specific markets. For example, the office category has one of the steepest and earliest declines which suggests that it is one of the riskiest and therefore additional coverage may be warranted.

Eric Gaus is Chief Economist at Dodge Construction Network, where he directs economic research. He brings over 15 years of experience in academia and the private sector, creating macroeconomic models and producing research on critical issues for the global economy. Prior to joining Dodge, Gaus was a Director at Moody’s, where he managed the development and maintenance of their global forecasting model and served as the product manager of their country risk service. He received his PhD from the University of Oregon and spent several years teaching at small liberal arts colleges. While in academia, Gaus published articles on the role of expectation formation in macroeconomics and finance. He can be reached at Eric.Gaus@construction.com.

Eric Gaus is Chief Economist at Dodge Construction Network, where he directs economic research. He brings over 15 years of experience in academia and the private sector, creating macroeconomic models and producing research on critical issues for the global economy. Prior to joining Dodge, Gaus was a Director at Moody’s, where he managed the development and maintenance of their global forecasting model and served as the product manager of their country risk service. He received his PhD from the University of Oregon and spent several years teaching at small liberal arts colleges. While in academia, Gaus published articles on the role of expectation formation in macroeconomics and finance. He can be reached at Eric.Gaus@construction.com.

Get Important Surety Industry News & Info

Keep up with the latest industry news and NASBP programs, events, and activities by subscribing to NASBP SmartBrief.